Introduction: Life in the Harshest Environments

Deserts are some of the most extreme and unforgiving ecosystems on Earth. With high temperatures, minimal rainfall, and intense sunlight, life in these environments must adapt to survive under some of the harshest conditions imaginable. However, even in these barren landscapes, life thrives in remarkable ways.

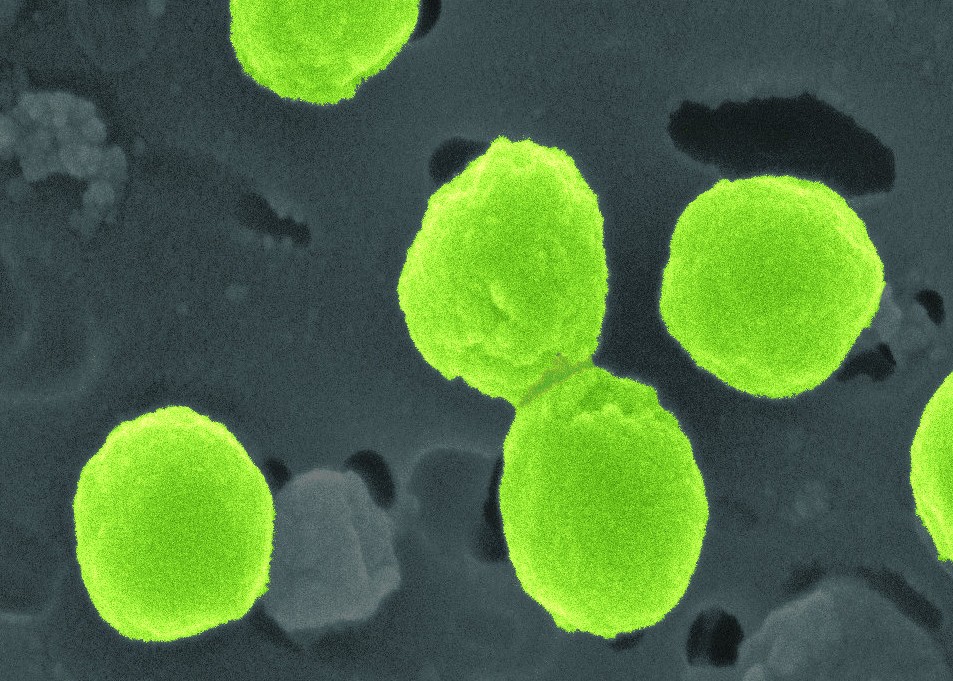

One of the most fascinating examples of life’s resilience in deserts can be found within the rocks themselves. Hidden beneath the dry, sun-baked surface, microscopic photosynthetic organisms, primarily cyanobacteria, can be found living inside rock crevices, absorbing sunlight, and converting it into energy through photosynthesis. These photosynthetic bacteria, also known as lithophytic cyanobacteria, have developed unique adaptations that allow them to survive the extreme temperatures, low moisture, and high UV radiation of desert environments.

In this article, we will explore the remarkable world of photosynthetic bacteria living inside desert rocks, examining their biology, adaptations, and ecological roles. By understanding how these microorganisms survive and thrive in such an inhospitable environment, we can gain insight into life’s resilience and the possibility of life in other extreme environments, both on Earth and beyond.

1. The Desert Environment: A Challenge for Life

1.1 Characteristics of Desert Ecosystems

Deserts cover about one-third of the Earth’s surface and are characterized by a combination of extreme conditions:

- High temperatures: Deserts experience some of the highest temperatures on Earth, often exceeding 40°C (104°F) during the day. At night, temperatures can drop dramatically, leading to extreme temperature fluctuations.

- Low precipitation: Deserts receive little rainfall, often less than 250 millimeters (10 inches) per year. In some areas, rain may not fall for years.

- High UV radiation: The lack of cloud cover and the angle of the sun mean that deserts experience intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which can be harmful to many forms of life.

- Arid soil: The soil in desert environments is typically dry and nutrient-poor, making it difficult for most plants and animals to survive.

Despite these challenges, deserts are home to a variety of life forms, from hardy plants like cacti to animals like lizards, rodents, and various insects. However, the most remarkable life forms are often the smallest and most resilient: microorganisms.

1.2 The Role of Lithophytic Cyanobacteria in Deserts

Among the most important groups of microorganisms in deserts are the lithophytic cyanobacteria. These bacteria are often found in rock surfaces, where they form a layer that is critical to their survival. Cyanobacteria are able to perform photosynthesis, a process by which they use sunlight to produce their own food, just as plants do. However, cyanobacteria have evolved unique adaptations that allow them to survive in environments where most plants would perish.

By living inside rock crevices or on rock surfaces, these photosynthetic bacteria are protected from the direct heat of the sun and the extreme temperature fluctuations that occur in desert environments. In this niche, they are also shielded from wind erosion, which would otherwise dry them out and strip away their nutrients.

2. Photosynthesis in Extreme Conditions: The Biology of Cyanobacteria

2.1 What Are Cyanobacteria?

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are a diverse group of microorganisms that have existed for billions of years. They are one of the oldest known forms of life on Earth and are responsible for some of the most important ecological processes, such as oxygen production and the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen.

Cyanobacteria are unique in their ability to perform oxygenic photosynthesis, which means they use sunlight to produce energy while releasing oxygen as a byproduct. This process is similar to what plants do, but cyanobacteria can thrive in a much wider range of environments, from the deep sea to the harshest deserts.

In desert ecosystems, cyanobacteria play an essential role in maintaining the ecological balance by contributing to soil fertility. They are involved in the cycling of nutrients, particularly nitrogen, by converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms that can be used by plants and other organisms. In some desert areas, they also help to stabilize the soil, preventing erosion and maintaining moisture.

2.2 How Cyanobacteria Survive in Deserts

Surviving in a desert is no easy task. The combination of extreme heat, intense sunlight, and lack of water makes life in this environment particularly challenging. Cyanobacteria that live in deserts have developed a series of adaptations to cope with these extreme conditions:

2.2.1 Moisture Retention and Dormancy

One of the biggest challenges cyanobacteria face in deserts is the lack of water. In response to this, cyanobacteria have developed a remarkable ability to retain moisture, often through a slimy sheath that surrounds the bacterial cells. This slime helps the cyanobacteria hold onto water and prevents dehydration during dry spells.

In addition, some cyanobacteria can go into a state of dormancy during periods of extreme dryness. During dormancy, the bacteria essentially “shut down” their metabolic processes, waiting for favorable conditions to return. Once moisture becomes available, such as after a rainfall, the cyanobacteria can “wake up” and resume their normal activities, including photosynthesis.

2.2.2 UV Radiation Protection

The intense UV radiation in desert environments can be harmful to most organisms. However, cyanobacteria have evolved mechanisms to protect themselves from the damaging effects of UV rays. One such mechanism involves the production of UV-absorbing pigments, such as scytonemin, which shield the bacteria from UV damage. These pigments absorb the UV light and convert it into harmless heat, preventing the DNA and other cellular components from being damaged.

Additionally, cyanobacteria living in desert environments often grow in dense mats or biofilms, which offer additional protection from UV radiation. The biofilm acts as a shield, absorbing much of the UV radiation and reducing the impact on the cyanobacteria below the surface.

2.2.3 Temperature Regulation

Deserts are known for their extreme temperature fluctuations, with daytime temperatures often soaring well above 40°C (104°F), while nighttime temperatures can plummet to near freezing. Cyanobacteria are capable of surviving these temperature extremes by being highly thermophilic (heat-loving) or by finding sheltered spots that buffer them from extreme heat. Many cyanobacteria in desert environments live within the crevices of rocks or the pores of soil, where temperatures are more stable than in the open desert.

These sheltered environments provide a microhabitat that shields the cyanobacteria from rapid temperature changes and prevents them from becoming desiccated due to excessive heat.

3. Ecological Role and Benefits of Cyanobacteria in Deserts

3.1 Nitrogen Fixation

Cyanobacteria are nitrogen-fixing organisms, meaning they can convert nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into forms that are usable by plants. This process is crucial in desert ecosystems, where the soil often lacks sufficient nitrogen. By performing nitrogen fixation, cyanobacteria contribute to the nutrient cycling in desert environments and help to fertilize the soil for other plants and microorganisms.

In some desert areas, cyanobacteria can form symbiotic relationships with plants or lichens, providing them with essential nitrogen while benefiting from the plant’s organic carbon produced through photosynthesis. These partnerships are particularly important in nutrient-poor desert soils, where other sources of nitrogen are scarce.

3.2 Soil Stabilization

Cyanobacteria also play an important role in soil stabilization. By forming biofilms on the surface of rocks or in the soil, they help to bind soil particles together, reducing the risk of erosion. This is particularly important in deserts, where strong winds can easily blow away loose soil, leading to desertification.

The biofilms formed by cyanobacteria also help to retain moisture in the soil, creating a more favorable environment for other microorganisms and plants to grow. This moisture retention is particularly valuable during dry periods when other sources of water are unavailable.

3.3 Supporting Desert Biodiversity

The photosynthetic bacteria in desert environments create microhabitats that support a wide range of other organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and invertebrates. By forming biofilms and interacting with the surrounding environment, cyanobacteria contribute to the complexity and biodiversity of desert ecosystems. In fact, in some desert environments, cyanobacteria are the primary source of energy for other organisms, forming the base of the food chain.

4. Implications for Astrobiology

The study of cyanobacteria in extreme environments, such as deserts, has important implications for the search for life beyond Earth. By understanding how these microorganisms survive in harsh conditions, scientists can better predict where and how life might exist on other planets and moons.

For example, Mars, with its arid, cold, and harsh environment, shares many similarities with desert ecosystems on Earth. Cyanobacteria and other extremophiles may provide valuable insights into the potential for life to exist in similar environments on Mars or the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, such as Europa and Enceladus.

Conclusion: A Testament to Life’s Resilience

The discovery of photosynthetic cyanobacteria living inside desert rocks highlights the incredible resilience and adaptability of life on Earth. These microorganisms have evolved unique strategies to survive in one of the harshest environments on the planet, proving that life can thrive in even the most extreme conditions. Understanding these adaptations not only enhances our appreciation for life on Earth but also helps us explore the potential for life in extreme environments beyond our planet.

In the future, as we continue to explore and study deserts and other extreme environments, the insights gained from these resilient organisms may also illuminate the possibilities of life elsewhere in the universe.