Introduction: The Mysterious World Beneath the Waves

The deep ocean is one of the least explored frontiers on Earth. Below the sunlit surface, where light cannot penetrate, lies a world of extreme conditions. Among the most fascinating features of this dark, pressurized world are hydrothermal vents—underwater geysers that spew superheated water rich in minerals and chemicals. These hydrothermal vents host some of the most unique and resilient life forms on the planet, organisms that have adapted to survive in environments that would be lethal to most other life forms.

The organisms that thrive near deep-sea hydrothermal vents are known as extremophiles, and they offer a glimpse into life’s remarkable ability to adapt to the harshest conditions on Earth. These vents, found at various depths in the world’s oceans, support chemosynthetic ecosystems that function without sunlight, relying instead on the energy provided by chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide, methane, and sulfur that are emitted from the vent fluids.

This article explores the types of extreme life forms found near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, their adaptations, and the broader implications for our understanding of life’s potential to exist in similar environments beyond Earth. We will also examine how these ecosystems provide critical insights into life’s resilience and adaptability.

1. Hydrothermal Vents: Earth’s Deepest Oases

1.1 What Are Hydrothermal Vents?

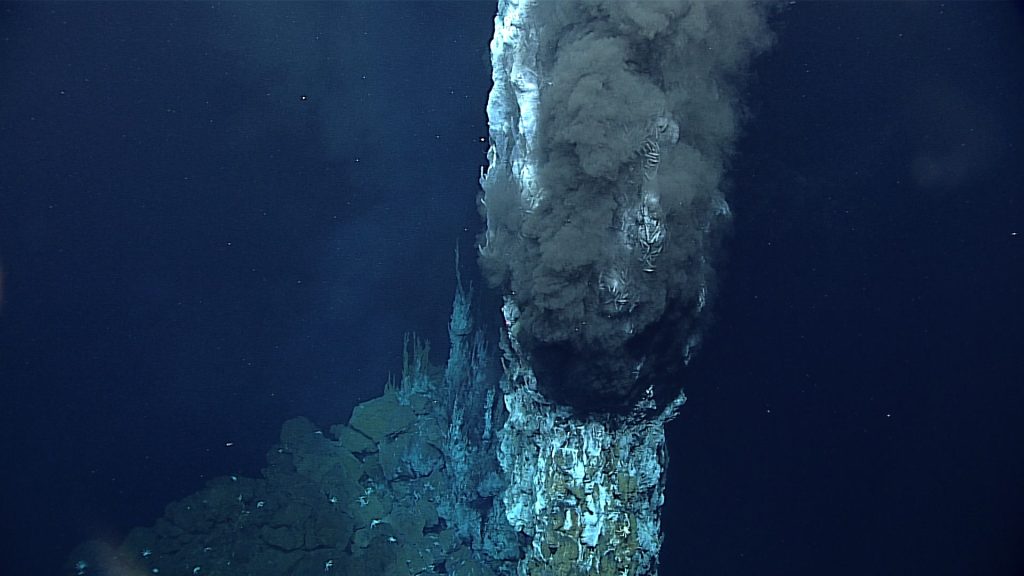

Hydrothermal vents are underwater geysers found on the ocean floor, typically along mid-ocean ridges where tectonic plates are either diverging or converging. They are areas where seawater seeps into the Earth’s crust, is heated by magma, and then rises back to the surface, carrying with it a cocktail of minerals and gases.

The fluid expelled from these vents can reach temperatures of up to 400°C (752°F), far hotter than the surrounding ocean water, which is typically just above freezing at these depths. These superheated fluids are rich in chemicals like hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), methane (CH₄), sulfur, iron, and copper, which are toxic to most organisms but serve as an energy source for the chemosynthetic life forms that thrive around the vents.

Types of Hydrothermal Vents:

- Black Smokers: These vents emit dark, mineral-rich plumes that are black in color due to the high levels of sulfide minerals suspended in the water. They are the most common and well-studied type of hydrothermal vent.

- White Smokers: These vents release cooler fluids than black smokers, and their plumes appear white because of the precipitation of minerals like barium and calcium.

Hydrothermal vents are typically found at depths ranging from 200 meters (656 feet) to over 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) below the ocean’s surface, making them some of the most remote and difficult-to-study environments on Earth.

1.2 Why Are Hydrothermal Vents Important for Understanding Life?

Hydrothermal vent ecosystems are significant for several reasons:

- Alternative to Sunlight: Unlike most ecosystems that rely on photosynthesis, hydrothermal vent ecosystems thrive without sunlight. This unique form of life sustenance is based on chemosynthesis, where organisms use chemicals like hydrogen sulfide instead of light to produce food.

- Analog to Extraterrestrial Life: The extreme conditions of hydrothermal vents, including high pressure, extreme temperatures, and a lack of sunlight, resemble environments that could exist on other planets and moons, such as Europa (one of Jupiter’s moons) or Enceladus (a moon of Saturn). Studying life at hydrothermal vents helps scientists understand the potential for life on other worlds.

2. The Life Forms of Hydrothermal Vent Ecosystems

2.1 Chemosynthetic Bacteria: The Foundation of Life

At the heart of every hydrothermal vent ecosystem is a group of bacteria that use the chemicals emitted by the vents for energy. These chemosynthetic bacteria are the primary producers in these ecosystems, much like plants are on land. They convert hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other chemicals into organic compounds that serve as food for other organisms.

Types of Chemosynthetic Bacteria:

- Sulfide-oxidizing bacteria: These bacteria use hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) from the vent fluids as an energy source, combining it with oxygen to create sulfur compounds. This process is crucial in supporting the food chain around the vents.

- Methanotrophic bacteria: These bacteria oxidize methane (CH₄) to produce food, which is especially important in methane-rich vent environments.

The bacteria form the base of a complex food web, supporting a range of organisms that rely on them directly or indirectly for sustenance.

2.2 Extremophilic Archaea: Ancient Survivors

Archaea, a group of single-celled microorganisms distinct from bacteria, are also a major player in hydrothermal vent ecosystems. These organisms are typically found in extreme environments, from volcanic hot springs to deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where they perform essential roles in chemosynthesis.

Key Roles of Archaea in Hydrothermal Vents:

- Methanogens: Archaea that produce methane from carbon dioxide, contributing to the energy flow in the ecosystem.

- Sulfate-reducing archaea: These archaea reduce sulfate (SO₄²⁻) to hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), a key component of chemosynthesis.

Archaea are known for their ability to survive in the most extreme environments on Earth, thanks to unique adaptations such as heat-stable enzymes that allow them to function in high-temperature environments.

2.3 The Role of Macroorganisms: Tubeworms, Clams, and More

While bacteria and archaea are the primary producers, larger organisms such as tube worms, clams, shrimp, and crabs are also found around hydrothermal vents. These organisms have adapted to rely on the chemosynthetic bacteria for food, forming complex symbiotic relationships.

- Giant Tube Worms (Riftia pachyptila): One of the most iconic creatures found near hydrothermal vents, these tube worms can grow up to 2 meters (6.5 feet) long and lack a digestive system. Instead, they host chemosynthetic bacteria inside specialized organs called trophosomes, which convert the chemicals from the vent fluid into food.

- Vent Crabs and Shrimp: These crustaceans often feed on the chemosynthetic bacteria directly or scavenge other vent organisms. Some species, like the vent shrimp, have evolved to withstand the extreme temperatures near the vents.

- Clams and Mussels: Like tube worms, these mollusks rely on chemosynthetic bacteria in their gills to process chemicals like hydrogen sulfide into organic nutrients.

These organisms form a complex food chain that exists without the need for sunlight, entirely dependent on the vent’s chemical energy.

3. Survival in Extreme Conditions: Adaptations of Vent Life

3.1 Adaptations to High Temperature and Pressure

The extreme conditions of hydrothermal vent environments—high pressure, high temperatures, and low oxygen levels—pose unique challenges to life. However, the organisms living here have evolved remarkable adaptations that allow them to thrive:

- Heat-Stable Enzymes: Many vent organisms possess heat-stable enzymes that allow them to carry out biochemical processes even in extreme temperatures. These enzymes are adapted to function at the elevated temperatures of the vent fluids.

- Pressure Resistance: Hydrothermal vents exist at depths where the pressure is several hundred times greater than at sea level. The organisms here are adapted to withstand this immense pressure through specialized cellular structures and membranes.

- Antioxidant Mechanisms: The high concentrations of chemicals like hydrogen sulfide and methane around hydrothermal vents can be toxic. Many organisms near the vents have developed antioxidant systems to detoxify these chemicals and prevent damage to their cells.

3.2 Symbiosis: Life Without Sunlight

One of the most fascinating aspects of hydrothermal vent ecosystems is the reliance on symbiosis. The larger organisms living near the vents do not have the ability to process the vent’s chemicals on their own; instead, they form symbiotic relationships with chemosynthetic bacteria. These bacteria reside within the tissues of the larger organisms, providing them with nutrients in exchange for a safe habitat and a steady supply of chemicals from the vent.

- Tube Worms: The giant tube worms mentioned earlier are prime examples of symbiosis. Their bacterial symbionts convert hydrogen sulfide into organic compounds, which the tube worms then absorb through their specialized tissues.

- Clams and Mussels: These mollusks also rely on symbiotic bacteria, which live in their gills and provide them with organic food from the vent’s chemicals.

4. Implications for Astrobiology and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

The study of life around hydrothermal vents provides valuable insights into the potential for life in extreme environments beyond Earth. The conditions at these vents—high temperatures, pressure, and the absence of sunlight—are similar to those that may exist on other planets or moons, such as Europa, Enceladus, or Titan.

4.1 Life on Mars and Europa

Hydrothermal vents offer an Earth-bound analog to the conditions that might exist beneath the icy surfaces of moons like Europa, where liquid water is believed to exist beneath a thick ice crust. The potential for life to exist in such environments, relying on chemosynthesis, could dramatically expand the conditions under which life could survive beyond our planet.

4.2 Extremophiles as a Model for Extraterrestrial Life

The study of extremophiles—life forms that thrive in conditions considered extreme—helps scientists understand the potential for life to exist in other extreme environments. By studying the mechanisms that allow life to survive in the deep ocean, researchers gain a clearer understanding of how life might adapt to the harsh conditions of other worlds.

Conclusion: A Resilient and Mysterious Ecosystem

The life forms surrounding deep-sea hydrothermal vents are a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life on Earth. These organisms, which survive without sunlight, under extreme temperatures, and at immense pressures, provide a glimpse into the vast potential for life in some of the most hostile environments on Earth and beyond. The study of these extraordinary ecosystems not only enriches our understanding of Earth’s biodiversity but also serves as a key to unlocking the mystery of life on other planets.