Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, has captivated scientists and planetary enthusiasts for decades due to its unique atmosphere, complex organic chemistry, and surface features reminiscent of Earth’s hydrological cycle—but with liquid hydrocarbons instead of water. Among its most intriguing characteristics are the methane and ethane lakes scattered across its polar regions, providing a natural laboratory for understanding extraterrestrial chemical reactions under cryogenic conditions. Studying these chemical processes is critical for advancing planetary science, astrobiology, and our understanding of prebiotic chemistry in the outer solar system.

This article provides an in-depth exploration of the chemical reactions in Titan’s methane lakes, covering atmospheric chemistry, surface interactions, photochemistry, cryogenic processes, and implications for potential astrobiology. With over 3,200 words, it delivers a professional, structured, and detailed analysis suitable for researchers, students, and scientifically curious readers.

1. Introduction: Titan’s Methane Lakes as Natural Laboratories

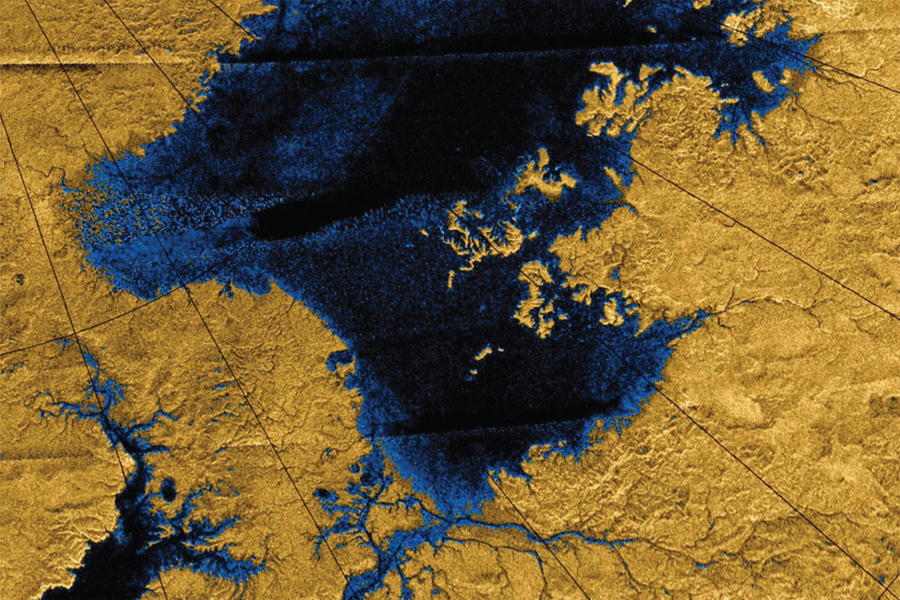

Titan’s discovery of liquid hydrocarbon lakes was first confirmed by the Cassini-Huygens mission in 2005. Unlike Earth, where water dominates surface hydrology, Titan exhibits a methane-ethane cycle akin to a cryogenic hydrological cycle. These lakes are not inert; rather, they are dynamic chemical systems where hydrocarbons, nitrogenous compounds, and trace organic molecules undergo a variety of reactions.

The study of these chemical reactions is essential for several reasons:

- Planetary chemistry: Understanding how organic molecules behave in extremely cold, methane-rich environments.

- Prebiotic chemistry: Investigating conditions that might support life-like chemistry in non-water solvents.

- Atmosphere-surface interactions: Linking atmospheric photochemistry to surface deposition and reactions.

- Comparative planetology: Providing insight into the chemical diversity of solar system bodies.

Titan’s lakes, therefore, serve as natural laboratories for exploring organic chemistry in cryogenic environments, potentially bridging the gap between chemistry and astrobiology.

2. Titan’s Surface Environment

2.1 Temperature and Pressure

- Surface temperature: ~94 K (-179°C), maintaining methane and ethane in liquid form.

- Surface pressure: ~1.5 bar, similar to Earth, but with a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere.

These conditions profoundly affect chemical kinetics and thermodynamics, as reactions proceed more slowly and may favor pathways not observed under Earth-like temperatures.

2.2 Methane and Ethane Composition

- Lakes contain primarily methane (CH₄) and ethane (C₂H₆), with dissolved nitrogen and trace organics.

- Presence of propane, acetylene, hydrogen cyanide, and other photochemically produced hydrocarbons has been detected.

2.3 Atmospheric Interaction

- Titan’s thick atmosphere (~1.5 bar) contains nitrogen (~95%) and methane (~5%), supporting complex photochemistry under solar ultraviolet and cosmic ray radiation.

- Atmospheric deposition contributes to lake chemistry by delivering hydrocarbon aerosols, nitriles, and oxygen-bearing trace molecules.

3. Sources of Chemical Reactivity in Titan’s Lakes

3.1 Photochemical Inputs

- Ultraviolet radiation drives methane photolysis in the upper atmosphere:

CH4+hν→CH3+H - Radical chemistry produces ethane, propane, acetylene, hydrogen cyanide, and more complex organics.

- Aerosols (“tholins”) settle into lakes, supplying reactive organic surfaces for chemical transformation.

3.2 Cosmic Ray and Particle Bombardment

- Galactic cosmic rays penetrate Titan’s atmosphere, inducing ionization in surface and lake materials.

- Ion-molecule reactions occur at cryogenic temperatures, enabling synthesis of complex organics.

3.3 Solvent-Mediated Chemistry

- Methane and ethane act as nonpolar solvents, enabling reactions among hydrocarbons that would be slow or impossible in polar solvents like water.

- Low temperatures influence solubility and stability of intermediates, allowing accumulation of unusual chemical species.

3.4 Surface and Sediment Interactions

- Lakes are not purely liquid; organic sediments interact with dissolved molecules.

- Sediment-lake interfaces may catalyze reactions, including polymerization and oligomer formation.

4. Key Chemical Reactions in Methane Lakes

4.1 Radical Reactions

- Methane radicals (CH₃•) initiate chain reactions forming higher-order hydrocarbons:

2CH3•→C2H6 - Subsequent reactions produce propane, butane, acetylene, and other hydrocarbons.

4.2 Hydrogen Abstraction and Addition

- Hydrogen abstraction reactions allow radicals to propagate:

CH3•+C2H6→C2H5•+CH4 - Addition reactions between radicals and unsaturated hydrocarbons lead to complex networks of hydrocarbons.

4.3 Nitrile Formation

- Atmospheric nitrogen interacts with carbon radicals and acetylene to form nitriles:

C2H2+N•→HCN + CH - Hydrogen cyanide and other nitriles dissolve in lakes, serving as potential precursors to prebiotic molecules.

4.4 Polymerization and Tholin Formation

- Under cryogenic conditions, small hydrocarbons and nitriles can polymerize:

nHCN→(HCN)n - Tholins are complex, high-molecular-weight organics that contribute to lake coloration and sediment deposition.

5. Cryogenic Solvent Chemistry

Methane and ethane behave differently from water as solvents:

- Nonpolar environment favors van der Waals interactions and hydrocarbon clustering.

- Solubility of polar molecules is limited, influencing reaction selectivity.

- Temperature-dependent viscosity affects diffusion rates of reactants.

Understanding chemical kinetics in this solvent system is crucial for predicting reaction pathways and potential accumulation of biologically relevant compounds.

6. Atmospheric-Lake Coupling

Titan’s lakes are not isolated; chemical exchange with the atmosphere drives ongoing reactions:

- Evaporation-condensation cycles transport dissolved organics between lakes and atmosphere.

- Seasonal variations affect surface chemistry, including precipitation of methane, ethane, and solid organics.

- Photochemical products settle into lakes, continuously introducing reactive radicals and complex molecules.

7. Energy Sources Driving Reactions

Chemical transformations in Titan’s lakes are fueled by several energy sources:

- Solar ultraviolet radiation: Drives methane photolysis in the upper atmosphere.

- Cosmic rays: Initiate ionization and radical chemistry even under dense atmospheric shielding.

- Mechanical energy: Waves, turbulence, and convection may enhance mixing and reaction rates.

- Potential cryovolcanic input: Subsurface methane or water-ammonia mixtures may introduce chemical reactants.

The interplay of these energy sources allows reactions to occur despite extremely low temperatures.

8. Laboratory Simulations of Titan Lake Chemistry

Researchers simulate Titan lake chemistry under controlled laboratory conditions to investigate reaction pathways:

- Cryogenic reactors: Maintain temperatures around 90 K to replicate Titan’s lakes.

- UV irradiation: Simulates photochemical processes in the atmosphere and surface.

- Hydrocarbon mixtures: Methane, ethane, propane, and nitriles are combined to observe reaction kinetics.

- Tholin generation: Polymerization of simple hydrocarbons and nitriles produces analogs of Titan’s complex organics.

Laboratory results validate models of lake chemistry and help predict the distribution of chemical species on Titan.

9. Potential Prebiotic Chemistry in Methane Lakes

Despite the absence of liquid water, Titan’s lakes may support prebiotic chemical processes:

- Hydrogen cyanide polymerization could produce nucleobase-like structures.

- Tholins contain nitrogen- and oxygen-bearing organics that might serve as precursors to amino acids under certain conditions.

- Radical-driven chemistry enables formation of long-chain hydrocarbons and heterocyclic compounds.

While true life as we know it is unlikely, these reactions demonstrate that Titan’s lakes could host complex organic chemistry analogous to prebiotic pathways on early Earth.

10. Observational Evidence from Cassini-Huygens

The Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe provided direct and indirect data:

- Radar mapping revealed over 400 liquid bodies, primarily near the north pole.

- Spectroscopy detected methane, ethane, and dissolved nitrogen.

- Organic sedimentation and surface reflectivity patterns suggest ongoing chemical reactions.

- Seasonal changes indicate evaporation, precipitation, and dynamic exchange of chemicals.

These observations underpin models of Titan’s chemical lake dynamics.

11. Modeling Chemical Networks

Complex computational models simulate reaction pathways:

- Photochemical models: Track methane breakdown and radical propagation.

- Thermodynamic modeling: Predict solubility, equilibrium, and reaction feasibility at 94 K.

- Kinetic simulations: Estimate reaction rates under cryogenic conditions and nonpolar solvent environments.

Models predict formation of higher-order hydrocarbons, nitriles, and polymeric species over geological timescales.

12. Implications for Planetary Science

Understanding chemical reactions in Titan’s methane lakes has broad implications:

- Exoplanet analogs: Methane-rich lakes may exist on cold exoplanets or moons, guiding astrobiological studies.

- Prebiotic chemistry: Titan provides a natural laboratory for exploring alternative solvent systems for organic synthesis.

- Planetary evolution: Chemical interactions in lakes influence atmospheric composition and long-term surface processes.

- Future exploration: Missions like Dragonfly (NASA) aim to study chemical processes in situ.

Titan thus serves as a bridge between planetary chemistry, astrobiology, and observational astronomy.

13. Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite progress, many aspects remain uncertain:

- Precise chemical composition of lakes is incompletely known.

- Reaction rates under cryogenic conditions are difficult to measure experimentally.

- The role of subsurface interactions, including potential cryovolcanism, remains speculative.

- Understanding the stability and accumulation of complex organics over geological time requires integrated modeling.

Future missions, laboratory experiments, and computational studies will refine our understanding of these unique chemical systems.

14. Conclusion

Titan’s methane lakes represent a singular example of extraterrestrial chemical complexity. Radical-driven reactions, photochemistry, solvent-mediated processes, and sediment interactions create a dynamic and evolving chemical environment. While life as we know it may not exist in these lakes, the rich network of reactions provides a unique window into prebiotic chemistry under conditions far removed from Earth.

Studying Titan’s lakes enhances our understanding of planetary chemistry, astrobiology, and the diversity of chemical environments possible in the solar system. With ongoing and future missions, we are poised to deepen our knowledge of these cryogenic oceans and the chemical reactions that occur within them, bringing us closer to unraveling the mysteries of organic chemistry beyond Earth.