Introduction: A World of Extremes

The Antarctic Dry Valleys, a vast and remote region on Earth, are among the harshest environments known to support life. With little precipitation, extreme temperatures, and an absence of vegetation, these valleys are often compared to Mars and other celestial bodies for their desolate conditions. Despite these challenges, microorganisms thrive in this seemingly inhospitable environment, providing scientists with crucial insights into the adaptability of life and the potential for life beyond Earth.

The Dry Valleys are a unique and isolated region in Antarctica, and they host some of the most resilient life forms on the planet. Microbial communities, particularly bacteria, fungi, and archaea, persist in the soil, glaciers, and salt lakes, relying on highly specialized adaptations to survive in this extreme habitat. These organisms endure temperatures as low as -50°C (-58°F), near-total darkness for months at a time, and minimal nutrients.

This article delves into the remarkable microbial life found in the Antarctic Dry Valleys, exploring how these microbes survive and thrive in one of the most extreme environments on Earth. It also looks at the implications of these findings for understanding life’s potential on other planets.

1. The Antarctic Dry Valleys: A Hostile Yet Fascinating Environment

1.1 Geography and Climate of the Dry Valleys

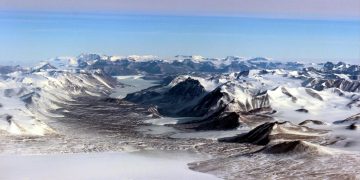

The Antarctic Dry Valleys are located on the western side of the Transantarctic Mountain Range, covering an area of approximately 4,800 square kilometers (1,850 square miles). These valleys, including McMurdo Dry Valleys, Victoria Valley, and Taylor Valley, are the driest places on Earth, receiving less than 2 cm (0.8 inches) of precipitation annually—mainly in the form of snow or ice that quickly sublimates due to the dry air.

The climate is polar desert-like, characterized by extreme cold, intense winds, and long periods of darkness. Winter temperatures can drop below -50°C (-58°F), and summer temperatures rarely exceed -20°C (-4°F). The soil is frozen for much of the year, and even during summer, only a small portion of the ground thaws.

Despite these harsh conditions, the Dry Valleys support microbial life, which has evolved over millennia to adapt to the extreme environment.

1.2 Why the Dry Valleys are Ideal for Studying Microbial Life

The Antarctic Dry Valleys have been referred to as one of the most Mars-like environments on Earth. They provide a unique natural laboratory to study life in extreme conditions and can help scientists understand how organisms might survive on other planets or moons with harsh climates and limited resources.

Several factors make the Dry Valleys a valuable site for microbial research:

- Minimal Human Impact: Due to their remote location and harsh climate, the Dry Valleys remain largely untouched by human activity, providing a pristine environment for studying natural ecosystems.

- Isolation: The microbial communities in the Dry Valleys are isolated from other ecosystems, making them ideal for studying how life can adapt to such extreme conditions without the influence of neighboring habitats.

- Extremes in Temperature, Radiation, and Nutrients: The environment is characterized by extreme cold, limited sunlight, and scarce nutrients, which provide insights into the limits of life’s adaptability.

2. The Microbial Residents of the Antarctic Dry Valleys

2.1 Types of Microbial Life Found in the Dry Valleys

Despite the challenging environment, a variety of microorganisms have been identified in the Dry Valleys, including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and cyanobacteria. These organisms have developed unique strategies to cope with extreme cold, desiccation, and limited nutrient availability.

Bacteria and Archaea: The Pioneers of Life

Bacteria and archaea are the dominant forms of microbial life in the Dry Valleys. These microbes are incredibly versatile and can survive in the harshest of conditions, such as the frozen soil of the valleys, the salty surface of glaciers, and even in salty, hypersaline lakes. Some of the most notable types of microorganisms include:

- Psychrophiles: These are cold-loving microbes that thrive in temperatures well below freezing. They possess specialized enzymes that function at low temperatures, allowing them to metabolize nutrients and grow in the frigid conditions of the Dry Valleys.

- Halophiles: Microorganisms that thrive in salty environments, halophiles have adapted to survive in the highly saline conditions of the dry valley lakes. These organisms have evolved mechanisms to balance the osmotic pressure caused by the salt and prevent dehydration.

- Lithotrophs: Some microbes in the Dry Valleys are lithotrophs, meaning they obtain energy from inorganic compounds like iron or sulfur. These organisms do not rely on sunlight but instead utilize the minerals found in the soil, glaciers, and salt lakes to produce energy.

Cyanobacteria: Harnessing Sunlight in Extreme Cold

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are among the most resilient microorganisms in the Antarctic Dry Valleys. They can photosynthesize and are found on the surface of rocks, in frozen soils, and in water sources that experience some sunlight during the Antarctic summer. Despite the limited sunlight, these organisms can survive and even reproduce, utilizing the available light to produce their own food.

3. Survival Strategies: How Microbes Thrive in the Dry Valleys

3.1 Extreme Cold Adaptations

The most obvious challenge faced by life in the Dry Valleys is the extreme cold. Many microorganisms in this region are psychrophilic (cold-loving) and have evolved a variety of specialized mechanisms to survive:

- Antifreeze Proteins: Some microbes produce antifreeze proteins that prevent their cellular structures from freezing by lowering the freezing point of water inside their cells. These proteins allow the organisms to maintain their metabolic processes even in subzero temperatures.

- Enzyme Adaptations: The enzymes of psychrophiles are uniquely adapted to function in cold environments. These enzymes are more flexible than those of warmer organisms, allowing biochemical reactions to occur at lower temperatures.

- Cryoprotectants: Some microorganisms produce cryoprotectants, chemicals that prevent the formation of ice crystals inside cells. This helps to protect cell membranes and proteins from damage during freezing and thawing cycles.

3.2 Dealing with Limited Water and Nutrients

Water is incredibly scarce in the Dry Valleys, and what little there is often exists in the form of ice. Despite this, many microorganisms have developed strategies to survive in such arid conditions:

- Desiccation Tolerance: Many microbes can endure desiccation (drying out) by entering a state of suspended animation. In this state, metabolic activity is nearly halted, and the organism can survive without water for extended periods. When water becomes available, they can rehydrate and resume normal cellular functions.

- Nutrient Scarcity: With minimal nutrients available, many microorganisms in the Dry Valleys are chemotrophic, meaning they obtain energy by breaking down inorganic compounds in their environment, such as iron, sulfur, or methane, rather than relying on organic materials.

3.3 UV Radiation Protection

The Dry Valleys experience significant levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation due to the high altitude and the thin atmosphere over Antarctica. Microbes have developed mechanisms to protect themselves from this harmful radiation:

- UV-absorbing Pigments: Some microorganisms produce pigments that absorb UV radiation and prevent it from damaging their cellular components. These pigments, such as carotenoids, act as a shield against the harmful effects of UV exposure.

- DNA Repair Mechanisms: Many microbes possess sophisticated DNA repair enzymes that can repair the damage caused by UV radiation. These enzymes work to fix mutations and maintain the integrity of the microorganism’s genetic material.

4. Implications for Astrobiology: Life Beyond Earth?

4.1 Analogous Conditions on Mars and Other Planets

The extreme conditions in the Antarctic Dry Valleys provide a valuable analog for understanding the potential for life on other planets, particularly Mars. Mars, like Antarctica, has a cold, dry climate with very limited liquid water and intense UV radiation. The microbial life in the Dry Valleys may provide insights into how life could potentially survive on Mars or other icy moons like Europa.

4.2 Studying Extremophiles to Understand Life’s Limits

The study of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—has provided critical insights into the limits of life. These organisms demonstrate that life can exist in conditions once thought to be uninhabitable, and the unique adaptations they exhibit may help us understand how life could survive in extreme environments beyond Earth.

Conclusion: Life in the Harshest Environment

The Antarctic Dry Valleys are home to a remarkable diversity of microbial life, each of which has adapted in unique ways to survive the extreme conditions of cold, dryness, and nutrient scarcity. These microbes represent some of the most resilient organisms on Earth and provide critical insights into how life can endure in environments once considered inhospitable.

The study of these microorganisms not only enhances our understanding of life on Earth but also has profound implications for the search for life beyond our planet. As we continue to explore the farthest reaches of our solar system and beyond, the lessons learned from the microbial residents of the Antarctic Dry Valleys could prove invaluable in our quest to understand the limits of life itself.